Summer Filming 2022, Sequoia Burn

(Part 1 of 3)

This summer filming season we focused on just one thing. The sequoia burn in California in 2020 and 2021 that killed about 13,000 of the known 75,000 mature sequoias in all of existence, where in recorded history only several hundred sequoias have died, and most of them simply fell over.

Preparation took a little longer this year. Other work interfered. The Icemelter, our 2004 Suburban expedition vehicle with 260k miles, needed some tender loving cash poured all over it. Goodness knows we need a reliable vehicle in the wilds where we film.

Getting the rest of the gear ready was not much of a problem after camping in the Icemelter for ten years. Cleaning the garage so that we could organize gear was the hardest part. What a mess.

“Icemelter” is what my environmental colleagues have labelled our wilderness filmmaking vehicle, a custom trail Suburban with a lift, 33-inch all terrain tires, a performance chip and a few other mods; make a Texan proud. I had a custom lifted Honda CRV for four-wheel-drive work for a while but… AWD is not four-wheel drive unless it has a low range gear box. Cute ride, 30 mpg, but don’t do it if you plan on needing the security of real 4×4 in the wilds. Trail work is hard on equipment, it’s not as innocent as it looks in commercials.

We, me and my wife partner boss, sleep in the Icemelter on 4 inch heavy duty foam pads. It’s nice. And importantly, it’s bear proof too. We call it our rapid filming response vehicle because making and breaking camp is so fast and easy. Put the gear boxes on the front seats, lay those big pads down in the back and pull out the sleeping bags. Viola – camp.

Dinner spot for the evening, 12 miles down Boulder Creek Grove Road, Kings Canyon in the Background.

Dinner spot for the evening, 12 miles down Boulder Creek Grove Road, Kings Canyon in the Background.

It takes five minutes if we are hungry or ready to get on the road. Coffee, bagels and go. We did 16,000 miles in 45 days with 43 camps in 2018, from Austin to the North Slope of Alaska via the California climate mayhem. That’s an average of 355 miles per day; climate change impacts almost the entire way. See our trip report here.

And what about climate change impacts from with such a beast as the Icemelter? When we bought our Prius I finally had a justification that could be understood; “What? Take the Prius to the Arctic Circle?” The road we are on above is deceiving. California is deceiving. Los Californios pave a lot of their most minor forests roads, at least up there on the rim of Kings Canyon even though absolutely nobody knows about these roads but a few forest service personnel and a few diehards. We saw not a soul on this road even though it is paved, in the four hours we were out. It is extremely curvy and slow. At the end though, to get to Boulder Creek Grove, the road changes to a classic mountain 4×4 trail. It’s steepness required low range crawling and it included rocks the size of a yearling bear, all making it impassable in normal SUV all wheel drive. And after a couple of hours we didn’t even find the grove because the 4×4 trails simply erupted into a maze.

To get from Texas to California this trip we decided to take Interstate 40 across the West. Interstate 10 through Chihuahuan and Sonoran deserts is fabulous, but we yearned for the mountains. It was hot in Texas. We were on about day 65 of 100-degree plus days so far this summer when we launched.

A herd of pump jacks in the Texas Panhandle.

A herd of pump jacks in the Texas Panhandle.

Three hours into the trip we were at San Angelo and time for lunch. We stopped across the street from where my wife Jeannie, trail name DJ, worked as a visually handicapped teacher just after she graduated from the University of Texas. We are a mixed couple by the way. I am a Texas A&M Aggie – Whoooop! Hullabaloo – Canek, Canek!

We gassed up on the west side of town, $3.48, not bad. It was $3.48 in Austin too. San Angelo is like the gateway to West Texas and it was open. The next thing we knew, we were riding among a sea of wind turbines spinning on the horizon, right up next to the highway, and everywhere in between. This country has always been so empty and quiet, a little bit of agriculture, a lot of cows, and little else.

Two hours later and we were in oil country around Abilene. Here, the pump jacks mix with the wind generators creating a somewhat counterintuitive landscape.

It was hot. The wind generators shimmied in the heat waves of West Texas.

It was hot. The wind generators shimmied in the heat waves of West Texas.

There are several free campgrounds in the panhandle area and we often stop for the night. Our favorite is at Coleman Park in Brownfield, a small agriculture community 35 miles southwest of Lubbock. About 10,000 souls are in Brownfield at an elevation of 3,300 feet. They have a huge city park like I remember from family reunions when I was a kid. It’s always quite a bit cooler in the evening in the Panhandle, the elevation and dryness cool it off, and there always seems to be a nice breeze. The coolness was especially nice after 65 days of 100-degree heat in Central Texas.

We were a few hours ahead of schedule, so on to New Mexico – up the highway we flew in Icemelter. Our destination was the small community of San Jon, New Mexico, about 20 miles west of the Texas border on Interstate 40 where there was a free city park. We arrived just after dark. It was a nice city park with one other camper. We picked a quiet spot and darn! Mosquitoes! After driving all day we were too tired to mess with the mosquito net to make the back of the Suburban mosquito proof, and it was too warm to sleep with the Icemelter’s lid shut, so we decided to cruise on to Tucumcari and get a motel.

Blue Swallow Motel, Tucumcari, New Mexico: Tucumcari is a freeze dried Route 66 community.

Tucumcari, New Mexico was a Route 66 regional agricultural center in the early and mid 20th century. Then the railroad closed their station in the 1960s. Then Route 66 was replaced by Interstate 40 that bypassed Tucumcari in 1984. Since, Tucumcari has all but blown away in the New Mexico dust. Until recently.

Within the last five to ten years, wind energy has come to Tucumcari. With a maximum population of 10,000, Tucumcari dwindled to 4,000 and now has grown again to over 5,000 because of that same wind that threatened to blow the entire community away just a few years ago. Tucumcarians now fancy themselves as the caretakers of a burgeoning art community. They have a tech college, four museums, scores of murals painted all over town, and a well preserved motor court art installation on the old Route 66 drag just off the interstate.

Tucumcari mural.

Tucumcari mural.

We have sped past this place scores of times between Austin and the Rockies on summer walkabout camping trips. Nary an idea did we have that Tucumcari was anything except a bunch of sad abandoned dreams withering in the New Mexico heat. Turns out, it is an exceptional bunch of old rundown buildings. You see, because of all the bypassing and reduction in agricultural demand, there has been no cause for redevelopment of the old rundown buildings. The have sat as they were in their heyday, only very slowly falling apart in the mummifying air. Route 66 in Tucumcari was frozen in time.

Now that there are real live people in Tucumcari again, with real businesses catering to the new wind generation economy, there is a need for things like motels. Old route 66 is awash in rehabilitated 80 years old motor courts. So give Tucumcari a second thought next time you come by. It’s still a little rank in the daylight on old Route 66, but downtown with all the murals is beautiful, and at night there’s a new crop of neon on the old byway, put there by new residents with a new dream.

Tucumcari mural.

Tucumcari mural.

Westward on Interstate 40 beyond Albuquerque the interstate was a blur, but mountains were near. Then to Gallup and beyond that corner in Winslow, Arizona to Flagstaff. We had our eyes on a campground not far off the Interstate near Williams, just west of Flagstaff in the Kiabab National Forest. It was raining those wonderful desert monsoons, cool and refreshing; jacket weather. Then the exit to Sedona appeared and southward we turned, previous plans preempted.

Beetle kill started showing up when we neared Flagstaff in the Coconino National Forest. It wasn’t horrid, but pretty bad in places and the attack extended south across the high country all the way to Oak Creek Canyon above Sedona.

Cedar killed from bark beetle or water stress, Sedona Arizona.

Cedar killed from bark beetle or water stress, Sedona Arizona.

Sedona; wow! How this place has changed in 30 years. What was once the metaphysical capital of the known universe has metamorphosed into a beautiful art installation. The New Agers are still around but they pale next to the art. Everything in Sedona, almost, is art. The cheapest motels, grocery stores, residences, along the community’s streets; all feature art as a statement. The art district is as insane as the scenery in Sedona, and almost as large as the rest of the community. The food? Art food. Yum! Don’t go to Sedona thinking you will find normal food though. Even the fast food is Sedonaized. The McDonald’s golden arches – not in Sedona, the arches there were turquoise of course!

Everywhere in Sedona is an art exhibit, even the food, beautiful and tasty too.

Everywhere in Sedona is an art exhibit, even the food, beautiful and tasty too.

We made an early start next day to give us a little time to wander the redrock wilds around Sedona. More change is what we found. The burbs of Sedona have spread far and many of the old four-wheel drive roads are now paved.

We did find some dirt, and headed away from civilization. What we found was more beetle kill, or possibly water stress mortality. In drought, it’s hard to tell as the conifers (pinyon pines and junipers in the lowlands around Sedona) don’t have enough water to create pitch to push the beetles out of their galleries. These pitch tubes as they are called, are common to beetle kill trees, where pitch literally oozes out of the holes bark beetles make in the bark. But with drought there is not enough water to create the sap to force the beetles out of their galleries so it is difficult to tell beetle kill from drought. Mortality was evident nonetheless. The kill was not extreme like on top of the Coconino Plateau, but it was present at many times normal mortality with both red and gray kill, where red kill is mortality from the last two or three years, and gray kill is after the needles have fallen and only tree bones remain.

Back to Interstate 40 and across Arizona to the Mojave National Preserve and Death Valley in California. The record monsoon rains had just shut down Death Valley National Park from flooding with damage that is expected to take more than a year to repair. We had a couple of hard monsoons pound us coming down out of the mountains into the desert, then again at Needles, one of the hottest places in the world. An 18-wheeler had just jackknifed and we spent an hour stopped on the interstate. Thank goodness for the rain as the temp was in the mid-80s where it could easily have been in the 100-teens.

John Wilkie Rest Area IH40, westbound Mohave National Preserve, Death Valley, CA.

John Wilkie Rest Area IH40, westbound Mohave National Preserve, Death Valley, CA.

The drive through Death Valley was surprisingly mild. Monsoon cloud remnants hung across what would have normally been a landscape shrouded in mirage.

John Wilkie Rest Area IH40, westbound Mohave National Preserve, Death Valley, CA.

John Wilkie Rest Area IH40, westbound Mohave National Preserve, Death Valley, CA.

We had made a travel time calculation error from Sedona to the Sierras. Boo. It’s ten hours from Sedona to Quaking Aspen Campground, not the six I had somehow messed up. On into the desert night we zoomed westward on IH40.

IH40 between Sheephole Valley Wilderness, Cleghorn Lakes Wilderness and Mohave National Preserve.

IH40 between Sheephole Valley Wilderness, Cleghorn Lakes Wilderness and Mohave National Preserve.

It was 120 miles to Barstow, another Route 66 community. When we arrived, various scenarios were playing out around homeless people who seemed to hang from every eave. We cruised town twice, up and down the main drag of old Route 66.

Route 66 Motel, Barstow, CA.

Route 66 Motel, Barstow, CA.

The homeless seemed to be concentrated on the east side of town where all the contemporary motels were located so we chose the two old route 66 motels on the west side that were not very well populated. The caretaker at Torches said we couldn’t have that room in the back corner we thought was nice with zero cars around, he said the only room available was the one up front next to his personal pickup. Well, it was a cool old place and what the heck. We were bushed. We paid the man his $60 bucks and started unloading important gear we never left in the Icemelter in a motel parking lot. Then, people started coming out of those rooms in the back with no cars. Strange people. Strange people doing strange things.

Torches Motel, Barstow CA.

Torches Motel, Barstow CA.

I was locking up after getting the camera bags, laptop and guitar. Jeannie was already sacked out. A pretty looking slim thing in a catsuit approached me from the general direction of the strange people coming out of the rooms where there were no cars. I said hello just to be friendly and maybe preclude a break in of the Icemelter later that night. I asked her the standard traveler’s questions, “Where you from and where you headed?” What came out of that catsuit’s face shocked me. I thought a 90 year old desert rat had spoken. She was from Baker, about 40 miles away, lived there all her life, “So boring” she said. Just then another of the strange people walked passed, pushing a grocery cart full of belongings. I said howdy, he didn’t turn his head or speak. After he was gone, catsuit was still standing there. I asked her what she did in Barstow. She said, “I’m a masseuse. I do full body massages.” Well…, that was enough. I excused myself and went into our room a few feet away, woke my sweetheart and asked if she had enough of a nap to get back on the road. We drove on another two hours to a roadside rest area somewhere in the desert night where we slept about four hours.

Next day, across Death Valley we sped, trying to get out of the lowlands before the oven weather set in. Solar PV installations were going in everywhere. Mile after mile of solar under construction broke the monotony of the desert scrub.

Then we started to climb up into the southern Sierra beyond the creosote bush flats to the strange world of the Joshua tree. Higher still was pinyon-juniper woodlands and at Isabella Walker Pass, ponderosa pine mixed in. The beetle and drought kill were pretty bad at the pass and fire had run through too.

Lake Isabella, Kern Co., CA. Once a 22 square mile lake. This is a boat ramp with courtesy dock.

Beyond the pass we crossed the Pacific Crest Trail and proceeded down into the valley of the South Fork of the Kern River. At Isabella Reservoir we turned north. The reservoir was almost dry. At 360,000 acre feet of storage in 2019, she was nearing 40,000 acre feet in California’s latest unprecedented drought. The tops of 67 year-submerged cottonwoods along the Kern and South Kern Rivers stuck up above water level.

The drive up the Kern River is always so hot and dry, but the river is generally a high volume affair that blasts down the valley with beautifully clear water from the High Sierra, cold and rocky: big rocks. It’s always been a powerful river in trips prior to this one. This year the white water was gone. The river itself was almost gone, replaced by black water and ashy sediment from the massive burn in the watershed from the 97,000 acre Windy Fire in 2021. Being hot and dry on the Kern River is not unusual, but the near absence of water was very unusual.

Kern River. Very low level with runoff from recent, rare summer rains that extinguished the Washburn and Oak Fires. These monsoon rains of the Sierra were not rare in our old climate.

Beyond Isabella we meandered up into the High Sierra and the Windy Fire. At first, and furthest south, there was moderate burn where red needles remained on the trees, and there was patches of unburned forest all around. This is a normal fire mosaic, normal in our old climate. A fire severity regime like this is sustainable,. It can clean up an over fueled forest to lessen the chance that fires become so extreme. But the “good” fire regime didn’t last. We were into extreme severity fire around just a couple of more corners.

Moderate and severe burns kill all trees, and needles show red or red-orange or are burned completely off with black trunks. Regeneration is better with low and moderate severity than extreme severity. But still problematic. Low severity burn has green remaining and normal regeneration capability, if it rains.

In an extreme burn, all the needles are burned off the trees, and all the duff and organic material is burned off the ground. Understory, perennials, grasses, the seed bank; all are burned down to mineral soil. Often with extreme severity fire the soil is rendered sterile and hydrophobic, or unable to easily absorb water.

Extreme burn, Windy Fire 2020. Extreme fire severity kills all trees, regeneration is problematic in many extreme burns today because of much drier conditions.

Extreme burn, Windy Fire 2020. Extreme fire severity kills all trees, regeneration is problematic in many extreme burns today because of much drier conditions.

The result of extreme severity burn is black runoff full of ash and carbon. Rainfall literally jumps down the mountain on the hydrophobic soils creating black walls of water in every slight watercourse. It smells like metal and flows like lava. Extreme severity fire accounts for 85 percent of total area burned in California today, where in our old climate it was 10 to 15 percent.

We drug into Quaking Aspen Campground with enough time to make dinner before dark. Gorgeous place. No giant sequoia but giant everything else. There was one patch of the camp that had a bit of fire from the KNP that literally jumped across the campground and burned the other side. There was also quite of bit of beetle kill. One small red fire about 8″ had thousands of beetle exit holes in its young bark. Across the camp road hung a green triangular beetle trap from another fir branch, empty. No beetles there.

Something I haven’t seen before at the campground was so much canker. Canker is a fungus disease that attacks a small part of limb after a bit damage from even an insect, or wind damage in winter. The fungus swells a small area of a 1 inch or smaller stem until it is two or three times its normal diameter and this causes the outer end off the limb to die and the needles turn red. This campground had more red tip die-offs than anywhere I had ever seen. Some trees likely had hundreds or or more red tips.

Red tip die off from canker in red fir.

Red tip die off from canker in red fir.

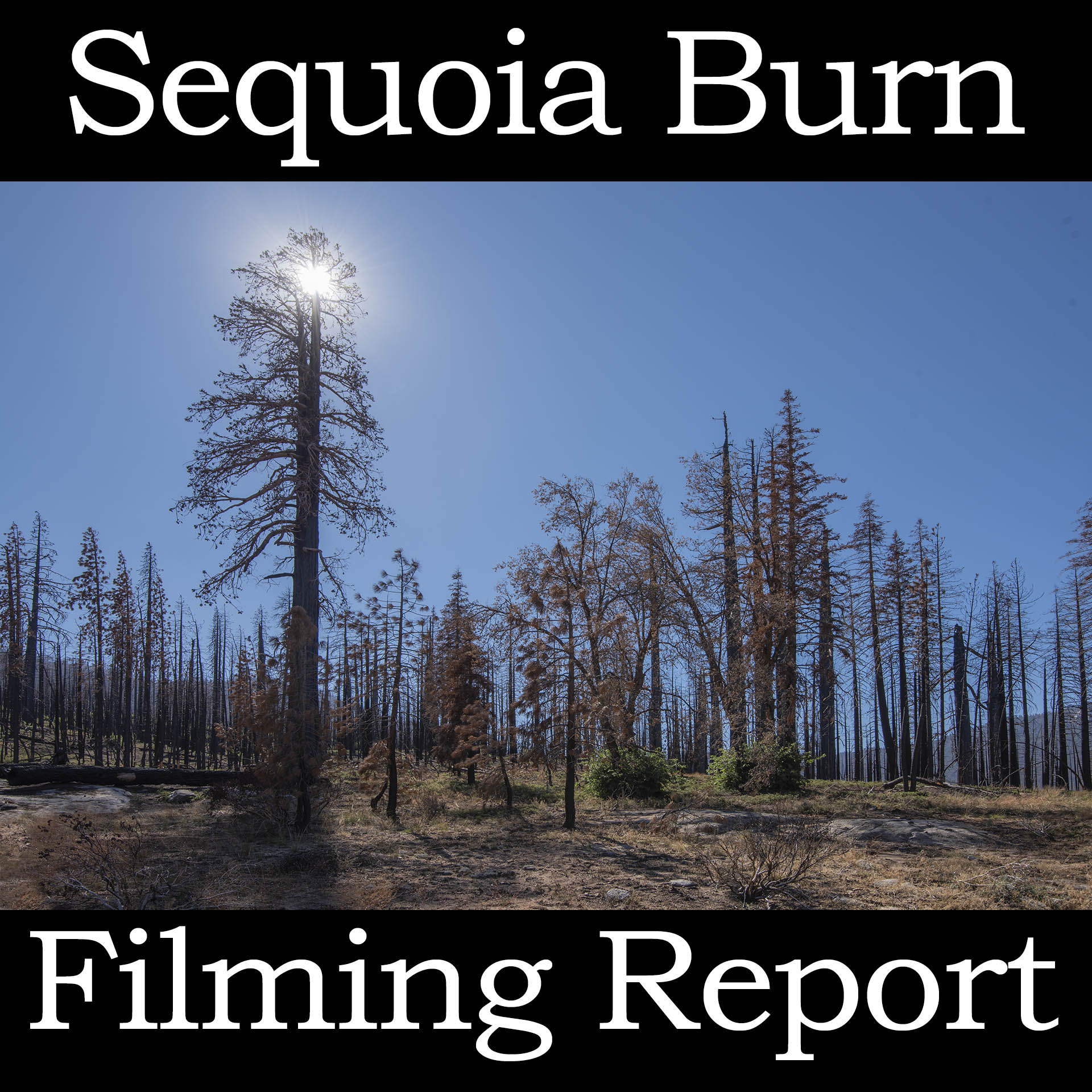

Sequoias are some of the most robust species on the planet capable of surviving anything mother nature can throw at them, in our old climate. Up to 13,521 mature sequoias were killed by wildfire between 2015 and 2021, with a total known population of only about 75,500 mature trees. Sequoias are notoriously fireproof with their giant stature, fire resistant bark, and lack of flammable resin production. Normally, sequoias do not burn. This is why they live to be thousands of years old, in our old climate. With six new extreme fire behaviors caused by warming, and excess fuels accumulation for a century or more from fire suppression efforts, the National Parks Service says a tipping point has been passed with this new sequoia mortality. We have entered an era where burned forests may not return unless we cool Earth to below the tipping point.

Giant sequoias greater than 10 feet diameter, 15 or more feet at 4 feet above ground. This extreme burn from the Castle Fire in 2020 spread across almost the entire Freeman Creek Grove. About 40 giants were killed in the small area I surveyed plus at least a couple hundred mature trees greater than 4 feet diameter. “Mature” is the scientific classification of a sequoia that is sexually mature and capable of reproduction.

Next day we headed straight for the biggest sequoia kill yet, the Castle Fire, a 170,648 acre fire up to 9,281 mature sequoias have now joined Mother Nature’s great tree heaven in the sky. A mature sequoia is one that is capable of reproduction at greater than 4 feet in diameter, of about 300 to 500 years old.

Freeman Creek Grove, Castle Fire 2020.- A single giant, 10 to 12 feet in diameter, about. The rest of the trees are 12 to 36 inches.

There are 70 giant sequoia groves in existence and more than 85 percent of grove area burned between 2015 and 2021. In the preceding 100 years, only 25 percent of grove area burned burned. The National Park Service says, “Large sequoias typically died by falling or, occasionally, having extensive crown scorch from fire. Death while standing, unrelated to crown scorch, was almost never observed by scientists who had spent decades working in the Sierra Nevada. And while mature giant sequoias did die from fire impacts; that were a relatively rare event, typically the result of many accumulated injuries over their long lives.”

Freeman Creek Grove, Castle Fire 2020 – The National Park service says we have now crossed a tipping point with sequoia forests. The extremeness of this burn is evident in that two years later there is still virtually zero regeneration of any species.

The National Park Service tells us, “The hotter drought of 2012-2016 appears to have been a tipping point for giant sequoias and other Sierra Nevada mixed-conifer forests. In hotter droughts, unusually high temperatures worsen the effects of low precipitation, resulting in greater water loss from trees and lower water availability. This is an emerging climate change threat to forests.” This current drought pulse is significantly more extreme than 2012-2016.

Freeman Creek Grove, Castle Fire 2020 – the scale is the giants is hard to visualize. REmember the rest of the forest is a normal forest with trees averaging two or three feet in diameter.

The reason why wildfire has moved through a tipping point is mostly dryness. Warmer temperatures increase evaporation from plants, soils and water bodies nonlinearly, as in: a little warming doesn’t create a little more evaporation, it creates a lot more. This means that with normal and even above normal precipitation, drought can persist because evaporation increases nonlinearly with increasing warmth.

Freeman Creek Grove, Castle Fire 2020 – Sequoias attain their great age because their asbestos like fire-proof bark can be two and even three feet thick. They do not have the structures that create flammable resins, and their great height puts their needles above the flames from fires in our old climate.

Specifically, the six fire behavior factors caused by climate change are: record dry fuels, a longer dry season with earlier spring and later fall, easier ignition with warmer temperatures, bigger wind storms, delayed onset of fall precipitation and increased nighttime fire behavior. Smokey Bear fire suppression does add a bit to increased fire behavior, but these six climate change enhanced fire behaviors are leading the list as to the reasons we are seeing such an astonishing increase in fire.

Freeman Creek Grove, Castle Fire, 2020.

Freeman Creek Grove, Castle Fire, 2020.

Smokey Bear Fires Suppression: Beginning in 1935, the US Forest Service set a goal of all fires being out by 10 am the morning following their discovery. In 1944, they introduced “Smokey Bear,” a young black bear cub rescued during WWII. Smokey was to become the new mascot of firefighting across the US. The resulting fire suppression has increased the number of trees in the forest, and increased understory growth that can act as a fire ladder to allow wildfire to reach tree crowns, as well as increasing fallen fuel on the ground.

“Freeman Creek Grove (4,192 acres), also known as Lloyd Meadow Grove, is the largest unlogged grove outside of a National Park. This grove is the easternmost grove of giant sequoias and is considered to be among the most recently established. The sequoias are mainly south of Freeman Creek with approximately 800 large trees (10 feet in diameter or more). There are several large sequoias to see in this grove. Foremost among these is the President George H.W. Bush Tree. President Bush delivered his presidential proclamation in 1992, setting aside giant sequoia groves on National Forest System lands for protection, preservation and restoration while standing beside a large giant sequoia at the bottom of the grove. You can visit the President George H.W. Bush Tree by taking Forest Road 20S78 east to the trailhead. There are a couple of trees with 20-foot diameters, more than 100 trees with 15-foot diameters, and over 800 with 10-foot diameters.” (From US Forest Service – https://www.fs.usda.gov/recarea/sequoia/recarea/?recid=79930)

It’s these six new fire enhancing behaviors however, that are driving these climate change-caused fires. If it weren’t for earlier spring and later fall creating a longer drying season, easier ignition with warmer temperatures, bigger wind storms, delayed onset of fall precipitation and increased nighttime fire behavior, these unprecedentedly large fires with similarly unprecedented severity, they simply would not be happening. What would be happening instead is a continuation of the slow increase in fire because of fire suppression strategies. Like the National Park Services says with sequoias, we have passed through a climate change tipping point with wildfire.

Since our climate has warmed out of the range of natural variability of our old climate in the last five to ten years, wildfires have become much more extreme and much larger. Wildfire was increasing before our climate reached this tipping point with forest fires, but over the last five to ten years the increase has been much more than the gradual increase from excess fuels accumulation. The reason why wildfire has moved through a tipping point is mostly dryness. Warmer temperatures increase evaporation from plants, soils and water bodies nonlinearly, as in: a little warming doesn’t create a little more evaporation, it creates a lot more. This means that with normal and even above normal precipitation, drought can persist because evaporation increases nonlinearly with increasing warmth.

It’s not just additional fuels from Smokey Bear fire suppression. Leading science says that climate change is not to blame because the dryness-caused increasing fire behaviors have created wildfire that is now 400 degrees hotter than in our old climate.